Let that sink in.

That is the genuine plot.

It is not followed by any subsequent contradiction.

Imagine being sat in a theatre for 90 minutes watching this. Feudalism, and then 'Victorian capitalism', have been killed by St. George - and the English, who had always been intrinsically good, are set

free.

Does that not sound a bit North Korea? Or a bit Enoch Powell? This is definitely the kind of patriotic bullshit Winston Churchill and Boris Johnson could share some racist jokes over.

|

| If this picture makes you feel something twingeing in your chest, and you're about to burst into a rendition of Elgar, then this is the play for you. |

Mullarkey's point seems to be that the native English are perfect, and their problems arise solely from corruption by external forces which need to be slain. Congratulations, dickhead, you've just invented xenophobic nationalism

and antisemitism in one go!

Seriously, Rory, surely it occurred to you? This plotline is the kind of thing Leni Riefenstahl would be commissioned to make. It's the national myth dozens of despots have relied on, and millions of people in human history have actually believed, and used to justify prejudices. And the one prejudice it rings most clearly of is antisemitism. So if you're going to give voice to Mosleyian ideas at the National Theatre, you'd better be doing this, Rory, just so you can mock those ideas?

But no, Rory, you don't take the piss of these ideas, do you? You actually write a story that confirms them. Because, Rory, in your story, after "the dragon" is killed, life does get better for the English, doesn't it?

And, instead of being aware of these connotations, you soldier right into antisemitic tropes, not wanting anything to get in the way of your pantomimic national myth-making. Your human embodiment of "capitalism", played by Julian Bleach - all Faginesque leering and top-and-tails opulence - reeks of tropes about Jews and money and power which we don't need to see repeated. And your play remains wedded to this narrative framework in which Bleach's external corrupter, who continues to look a lot like an antisemitic drawing of a Jew, is scary to the audience. He descends from a ceiling, lit up in a solo spotlight, and roars at the audience. I mean, how else am I meant to interpret that? You cannot claim to be mocking our fear of the outside corrupter of the English; you are encouraging it.

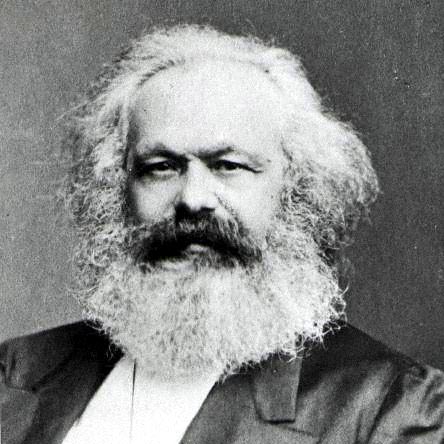

|

| An antisemitic caricature, very much like the one currently on display at the National |

I imagine you would answer that the dragon is not a literal being, but is in the minds of the English all along? But this is really a matter of semantics: you write as though the English are innately and originally pure, and then corrupted by an externality: whether that externality is a concrete bad person or a bad idea doesn't matter. This is pure McCarthyism: root out the poison, which has come from outside, into our people's heads. You still chose to embody the evil 'idea' as a possibly Jewish magnate pantomime baddie.

I don't believe Mullarkey perceives these connotations. But only because I'm not convinced he's thought very much at all about these metaphors, or is using them very effectively to drive home any kind of point.

Read any online review of the play, and you'll find a critic keen to tell you that Mullarkey "was inspired by" (read: copied) Evgeny Schwartz' 1943 play The Dragon. In that play, the "Dragon" of Russian Tsarism is slain, and then replaced by the "Dragon" of Stalinism. Fair enough, Schwartz. You've used a metaphor there to communicate a clear and precise analysis: that the Russian revolution led to a state as despotic as the one it overthrew. Great. Point made. Same analysis as in Animal Farm, but at least you've found an original way to say it.

Mullarkey's analysis is, on the other hand, nonexistent. What is he trying to say here? That the people of England threw off the shackles of feudalism and lived happily for a few years, but then were yoked again under the shackles of capitalism? Because if that's your analysis, it sounds like a drunk first-year student who hasn't read Marx trying to impress girls. What the hell kind of economic system do you imagine people lived in in between "the evils of feudalism" and "the evils of capitalism"? And what kind of system do you imagine you are living in now? When do you imagine we threw off the yoke of capitalism? What is this nonsense about the evils of "the system" being suddenly cured by an external, white, upper class hero? How are you putting that white-saviour nonsense on the stage and then not mocking it? Or are you trying to say capitalism erodes individuality even more than the feudalism that preceded it? Because it's a bit fucking ambitious to attempt to make such a heavyweight economic-historical point in a play which is 90% about fighting dragons.

All of this might sound like I'm trying to read too much into it, but you didn't give your audience the choice. You made a "dragon" tell us "he was the system" and then get killed when George destoys the statutes that uphold "the system". In Act Three, I've no idea what Mullarkey wanted the Dragon to represent, but

reviewers are falling over each other to claim it's "Brexit", because they too, saw that you wanted it to mean something. Time and again, I tried to just settle into my seat, buy into a character - any character - and enjoy the storytelling. But you wouldn't let me do this, Rory. You are adamant that we must listen to your points, wherever they are. The allusive language always returned, in lines like "the dragon is in us all". You can't not search for meaning in this play.

And let's be honest, Rory, if you take away all the meaning - if it really was just a play about dragon-killing - it would be a pretty weak story wouldn't it? "Man kills dragon twice then can't do it a third time." Not a very satisfying Shrek movie, that. You need it all to allude to something, Rory, otherwise you've just got a fairytale that ran out of puff. You would have just subverted the whole fairytale genre purely in order to remove the enjoyment.

I think what's happened, Rory mate, you wrote in the metaphorical significance of the Dragons, didn't you, and then you kind of forgot to follow the metaphor stuff through? I think you've got carried away with the actual Dragon-slaying storyline and you're enjoying the sub-Carry On fun that you think you can have on a series of historical adventures.

|

| There is more than a dash of Carry On's brand of silly, thoughtless historical adventure in Mullarkey's play. The problem is Mullarkey doesn't settle for that, and keeps trying to make it say something serious too. |

The reason I think this is that you poured so much energy and love and care into the actual swashbuckling. This was not ironic swashbuckling. This was not even sincere swashbuckling which is then cleverly upended by a self-contradictory ending. This was genuine swashbuckling, with both the 2 first acts providing the audience with a self-contained, traditionally-structured heroic story, for which we are never offered any alternative frame of reference other than the obvious one: a happily-ending underdog story.

A typical 'joke' in the play runs like this: George returns from killing a dragon, covered in blood. When he removes his armour, the red blood has created a cross on his white clothes, in between the armour, forming a St. George cross. The villagers then fly this fabric as a flag. And there you have it. The St. George flag.

What are you doing here, with this joke, Mullarkey? What is the substance behind this joke? Why are we positing hypothetical creation-myths for the St. George cross? There are only two possible reasons a playwright would do this joke. Either:

a) They genuinely would like a play to contain a half-joking, knowingly-fabricated creation-myth for the St.George flag. This is the Andrew Leadsom/American tourist option. The option whereby the playwright wants us to say "ooh yeah, isn't it fun to think about where these bits of our national culture could have come from. I know they didn't but imagine if the St. George cross came from that, that would be awesome!". This is the option that would appeal to a jibbering flag-waving simpleton.

Or ...

b) Because you want to mock the Andrea Leadsoms who would prefer option A. And that, if that were your reason for the joke, I would enjoy. Is that what is going on here, Rory? Are we mocking patriotism for its flimsy foundations? Is it like the

joke in Life of Brian where they all start worshipping a gourd by accident? Maybe you are actually assuming that all your audience find flag-waving a bit silly (which, in Britain in 2017, I think is a bit optimistic, but I admire your optimism) But if your intention really is to mock the baseless myth-creation of patriots, then I think you could have gone in a bit harder than just suggesting "your St. George flag was probably designed by accident!" You haven't mocked the flag-wavers very well there? You've told them something that they might actually quite like - that the flag was born out of bloody struggle. If you wanted to use your incredible platform to mock national myth-creation, then where was the follow-through, Rory!? How was that reflected in other jokes and in the moral and narrative framework of the play!? What you needed to have was some ironic moment where a pompous idiot stares up at the St. George cross with pride and comments on how carefully it's been designed or something? (Geddit? Even though it was designed by accident) Do you get me? Or you could had hordes of people worshipping George's blood-splattered cloak as a relic or something? I don't know, I'm not a comedian, but you only really did half the joke there, man. It's like if you said to me in person, "do you want to hear a joke? Why is the st. George cross flag red and white" And I said "why"? And you said "because St. George killed the dragon". I'd just be like "what? Is he alright? Is he actually into all this St. George, flag-waving patriotism stuff?"

|

| A joke that actually successfully takes the piss of hysterical worshippers. |

Maybe it's one of those 'jokes' where really, it's not a joke - just a reference to something. You know those ones? Like Peter Kay built a whole career out of. You just show us something we recognise on stage and we're supposed to clap like seals because we recognise it. "Oh look, that's clever", we're meant to say. Well apologies Rory, if that was the spirit it was intended in, because I just sat there waiting for the punch line about it.

I could see it's a St.George's cross on the white linen, Rory. Just like I could see you were playing with the fairytale genre. Just like I could see that the dragon represented something....